Case 7: Urban Sustainability/Redesigning the Urban Lifestyle

At 42, Arcosanti, a community north of Phoenix, Arizona has been celebrated, yet generally ignored, by the world at large. Nevertheless, the place that architect Paolo Soleri and his followers built in the desert, survives. Indeed, it can teach us enormously important lessons about cities, buildings, peo

ple, nature, and authenticity of place

Jeff Stein, AIA, is president of the Cosanti Foundation. He has taught at Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD), Wentworth Institute, and was dean of Boston Architectural College for seven years. He attended his first building workshop at Arcosanti in 1975. Here he gives some revealing answers about how an urban system can function as a super-organism, how historic context can shape a place and its life, as well as thoughts on the efficient use of land, growing plants and making moisture in the desert, and many other timely topics.

Jeff Stein, AIA, is president of the Cosanti Foundation. He has taught at Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD), Wentworth Institute, and was dean of Boston Architectural College for seven years. He attended his first building workshop at Arcosanti in 1975. Here he gives some revealing answers about how an urban system can function as a super-organism, how historic context can shape a place and its life, as well as thoughts on the efficient use of land, growing plants and making moisture in the desert, and many other timely topics.

Jared Green: Arcosanti is a living, experimental laboratory for the “arcology” theories of Italian architect, Paolo Soleri, who recently won the National Design Award for Lifetime Achievement. Arcology, a literal joining of the words architecture and ecology, calls for a new alternative to today’s “hyperconsumption,” a self-reliant urban system that functions like a super-organism. How are the theories of arcology working out in practice out here in the desert at Arcosanti?

Jeff Stein: They’re working out really well but at a very small level. Arcosanti, some 42 years after it first was begun in 1970, is just a tiny fragment of what it intends to become — a town for a few thousand people. Right now, we’re at a population of a little less than 100. It’s pretty easy at that small scale to join architecture and ecology, but we have in mind some bigger ideas. While they certainly come from Paolo Soleri, they also come from Henry David Thoreau.

Before I moved to Arcosanti this past year, my wife and I lived near Walden Pond for about a decade. The contrast between that place and this is pretty interesting, but the ideas that Thoreau and Soleri both have had are pretty congruous. Thoreau said, “Give me a wildness no civilization can endure,” which isn’t quite what we’re after exactly, but you could understand his attitude back then. There is wildness that no civilization can endure. Instead what we’re after is trying to create the beginnings of a civilization that wildness can endure.

Here at Arcosanti we’re only building on a few acres of a 4,000 acre land preserve. Some 3,985 of those acres are intended to remain wild. While at the center there isn’t a group of hermits but a lively cultural center. Arcosanti is meant for a few thousand people– not just as retirees living in apartments who have to drive 20 miles for groceries — but a living, working community whose architecture is gaining some light and heat in the wintertime and shading itself in the summertime, and whose solar greenhouses are recycling organic waste and growing food for the population and producing heat energy to power the town itself.

JG: You mentioned that the entire Arcosanti site is settled within an invaluable cultural landscape, including ancient pueblo dwellings and rock drawings. How does this historic landscape shape what you are practicing here today?

JS:It’s a fascinating and historic landscape, one that has been populated for thousands of years, and yet there’s almost no trace of the population of literally thousands of people, who over many, many years, have lived on this same spot where we’re sitting right now for this interview. It’s always been that way. I’m thinking now of a Spanish gentleman explorer, Alvar de Vaca, whose gallion was washed ashore near Galveston, Texas, around 1528. He and two of his companions walked around Texas. They went up into New Mexico back down to the Rio Grande in Mexico, between 1528 and 1536. They were never on their own by themselves ever in those eight years. They were always on well-trodden paths. There were trails. They were always well taken care of by people in villages and communities that they happened upon. It was an entirely settled landscape, and yet there’s almost no trace of those settlers at this time–only another 500 years later.

We’re trying to be cognizant of the historic landscape and preserve almost all of it. We can find out some things about the people who lived here before based on the little amount of ruins and petroglyphs and signs of their civilization that are still here, but we’re also somewhat trying to use them as a model for behavior. We’re not paving everything over with concrete and asphalt, and we’re not pumping all the oil out or digging all the coal out or transforming the landscape, except in a very tiny place where the center of this urban experiment, Arcosanti, is meant to be constructed.

JG: Arcosanti uses just 25 acres of its 4,000-acre compound. The idea is to show visitors how a compact community looks when it lives in a landscape, but doesn’t sprawl out or take it over. The built Arcosanti site is 15 acres, with much of that landscaped. How does the landscape architecture reflect the theories of arcology? What are the benefits of the landscape you use?

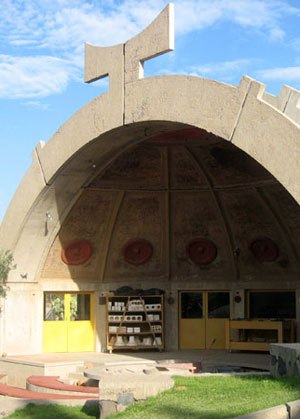

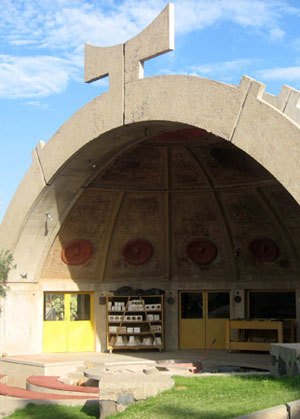

JS:The built landscape here is a working landscape. It’s not meant just to be viewed or walked through in a passive sort of way, but really functions, and relates to the buildings that it surrounds. The buildings are all about connection. Many of them have pretty rigorous curved shapes, and even some of them are in the form of the apse, a quarter of a sphere that when facing south, can shade itself in the summertime, and gather light and heat from the low winter sun. That curved form provides a really interesting social space in which people can experience each other. They can see each other work, people walking by. All these buildings at Arcosanti are about connecting people to each other and to a place.

The landscape architecture here isn’t trying, as it has to do in many cities, to soften the hard-edge built landscape or humanize it in some way. It is actually an outgrowth of it. A couple generations ago, Frank Lloyd Wright worked very hard in blurring the distinctions between inside and outside of his buildings. Even in his most modest houses, the Usonian houses, he would do things like drop a glass wall directly into a flower bed. The glass would extend to a foundation underneath the flower bed, but there are flowers growing inside. A big overhang would extend maybe six feet from the line of that glass wall so it was hard to tell if you were inside or outside. The landscape was making its way into the building, and yet your experience was making its way out of it. Paolo Soleri, the founder of Arcosanti, spent a year and a half working with Frank Lloyd Wright and took some of those interesting ideas away from his time with Wright.

The apse is attempting to construct a building that doesn’t separate you from your surroundings. The way it doesn’t do that is the fourth wall of the building is nonexistent. The apse provides shelter in which you can do most of your living and working out of doors year round in this climate: 3,700 feet, American Southwest. It works with the sun and seasons. The surrounding landscape becomes a part of your actual living space. You feel connected to the living things that are part of the landscape and to the landforms that have drawn you to this place.

Where we touch the earth with our architecture and landscape architecture, we really transform it into this urban condition of Arcosanti, but, otherwise, we’re leaving it alone entirely so that historic landscape that surrounds this place is in its natural form. Just lately, a film crew from Canada was here doing a piece from Canadian television about nature deficit disorder among young people in Western civilization. It’s a real and interesting issue in which young people aren’t outdoors, or if they are, they’re in this gridded rectilinear urban environment in which they don’t get a sense of seasons, plant life, or the patterns that nature provides. Back with Alvar de Vaca in Galveston, Texas, nature had always been the home of humans. We’re trying to rediscover what that means for us in miniaturized, densely-populated urban conditions that integrate nature and nature’s patterns into the living space.

JG: The dense urban core also includes some fascinating public spaces–amphitheaters, plazas, streets, and gardens. How has Soleri and his designers approached the landscape architecture in the denser, more trafficked areas?

JS: In the denser areas, there are moments where there are native plants growing right in front of somebody’s doorstep or trees that are grown for shade or for their fruit here and pretty well-tended, but, otherwise, it’s the desert areas or hardscape. In the tradition of an Italian hill town in which there aren’t streets and roads and parking lots within the populated townscape, there are pedestrian paths and stairways and sidewalks that are going through, but they’re hardscaped.

You can sit down almost anywhere. The walls of buildings are often designed so that they function as outdoor bleachers. The roofs of most buildings are accessible and you can get on top of them. There’s a little bit of roof gardening going on, but we don’t really have any substantial green roofs at Arcosanti yet. We have quite a few places that are earth-sheltered. We do harvest all the rainwater from our roofs. They slope at a really slight angle so that water can run off into cisterns. We use that for landscape watering.

JG: Since the 1970s, the city has only grown. In fact, it seems to be constantly evolving with a whole new set of projects just this year. Can you talk about the new “greenhouse apron” prototype? How does this help the community reach its goals related to food production?

JS: We’ve turned to greenhouses, an architectural solution for growing food. You don’t have to have thousands of acres of cropland out there to produce food for thousands of people. You can grow it very intensively in solar greenhouses, and in that case, it’s grown right on the doorstep of the town itself. The people who are, essentially, the farmers can be part of the town. They don’t have to live by their acreage, and because of the intensive style of tending the horticulture, you don’t need a lot of chemicals, insecticides, fertilizers.

We have a couple of small solar greenhouses attached to buildings here. One of them is attached to my apartment, and I can just open a little door in the bottom of my living room wall in the wintertime and this wonderfully fresh 120-degree air from plants and from the sun comes wafting into the apartment. It’s fragrant because plants are flowering, it is oxygenated because of the plants, and moist because the plants are transpiring moisture. Everybody should have this experience, but moisture is the main thing here. You can grow plants in a greenhouse, and as the plants transpire their moisture, it doesn’t get lost in the desert air, but it condenses again onto the greenhouse glass and can be recycled.

JG: More ambitious project initiatives are also in the works. The “critical mass” master plan calls for the ability to house 500 people full-time in this landscape and running the community. Vertical garden walls will be added to new residential complexes, while greenhouses would create new micro-climates that will enable more self-sufficiency in all seasons. What’s the big future vision for Arcosanti? Where do you see it in 25 years?

JS:You can do all the planning that you want, and we, certainly, are doing all the planning that we want to here on a daily basis at Arcosanti, but in the end, it’s conjecture. It’s dependent on so many outside forces. We’re not self-sufficient in terms of food growing, book publishing, clothes-making, or financial status here at Arcosanti. We have bootstrapped this entire project so far over 42 years by educational initiatives–the construction workshops, tourism, lectures, demonstrations, and the making of the famous Soleri wind bells as part of the economy here. We’re constantly looking for ways to expand the economy and for not only philanthropists, but for investors to become a part of the project. We have partners now among a series of colleges and universities that are doing projects involved with the notion of what if? What if Arcosanti became a global educational resource about sustainability, urban design, and landscape? Or what if it just turned out to be a Soleri museum? Or what if it became the corporate headquarters for something like Google?

There are design departments in a couple of different colleges in the U.S. and in Europe working with us on business plans and infrastructure design for those scenarios, but my own plan is for Arcosanti to continue its growth to become really a global educational resource and a national educational resource, too. I would like to start from the spark of Arcosanti a national discussion among American children and their parents about how cities should be designed — about how landscape architecture should actually work in urban areas, what it means to live in a city, and what it means to have wildness in the landscape outside of cities, too.

There’s a lot of talk about getting higher mileage for cars. Hybrid cars get maybe up to 50 miles per gallon–whoopee–but even so, the entire transportation sector of the U.S. only takes up a quarter of all the energy use in this country. Another quarter’s in manufacturing, mostly because we’ve sent much of our manufacturing to other countries, China included.

Half of all the energy used in America is used in buildings–in constructing them in the first place, but mostly in running them—heating, cooling, lighting them. So if you look up from your computer right now and look around you wherever you’re sitting in this country, you’re seeing obsolete buildings—buildings that we can no longer afford to support in terms of their energy use, and we certainly can’t afford to build many more of them. Yet, almost no one in the country, and certainly none of our politicians, is talking about any of this as an issue. It seems to us here at Arcosanti that it’s the main issue: how we design buildings, how they’re integrated into their landscapes, how cities are designed, not just for energy efficiency, of course, but for real sustainability at all levels of income. We use about one-sixth of the electricity at Arcosanti that most institutions of our size use. As a result, that’s five-sixths of electricity that we don’t have to pay for because we just don’t use it. We don’t have cars within our community.

Sixty percent of urban land in Phoenix is car-related.

If we’re able to change how we think about cities and cars as we hope to by sparking debate that begins here at Arcosanti, then there might be serious income available to build some truly wonderful things, and to live the kinds of wonderful lives that we’re just not able to live now because the patterns of our cities are so archaic.

Jared Greenis editor of The Dirt, the blog of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). The Dirt covers news on the built and natural environments.